Introduction

Much virtual ink has been put to the proverbial page examining the credentials of recently hired law professors.[1] Past analyses of the hiring market point to a few consistent trends – newly hired professors usually attended elite law schools before spending just a few years clerking and working as a fellow or Visiting Assistant Professor (VAP) at a law school.[2] The most up-to-date information on entry-level hiring comes from Professor Sarah Lawsky.[3] Each year since 2011, she has released a spreadsheet with information about the new hires and a report analyzing trends in the market.[4] Her dataset specifically tracks many of the metrics that have traditionally been deemed important for the hiring market.

Advice on the entry-level hiring market tends to be general, treating the market as a monolith. In reality, the overall market is far more heterogenous, made up of many subject-specific sub-markets. As a result, trends from the overall market likely do not hold up across every submarket.[5] While Prof. Lawsky’s reports are fantastic at illustrating trends in the market as a whole, there is little information analyzing these subject-specific sub-markets.[6] When I was first preparing to go on the market, I was surprised to find a dearth of information on the environmental law market.[7] Thus, in this Analysis, I explore the differences between the environmental law sub-market and the entry-level market as a whole. My goal is to inform prospective environmental law professors about the current state of hiring in environmental law. I also believe current environmental law professors and hiring committees will benefit from this knowledge.

I. Methods

Prof. Lawsky’s raw data includes specialty areas for each new hire, along with more general information about each professor’s credentials. As such, I used the spreadsheets provided by Prof. Lawsky to build a separate database of new professors hired each year that were at least nominally focused on environmental law.[8] I pooled the spreadsheets from 2011 to 2022, and I filtered out any new hires that did not include either “Environmental Law,” “Natural Resources Law,” or “Energy Law” as a specialty area. I also removed clinical hires to limit the analysis to doctrinal, tenure-track hires.

II. Overall Hiring Trends

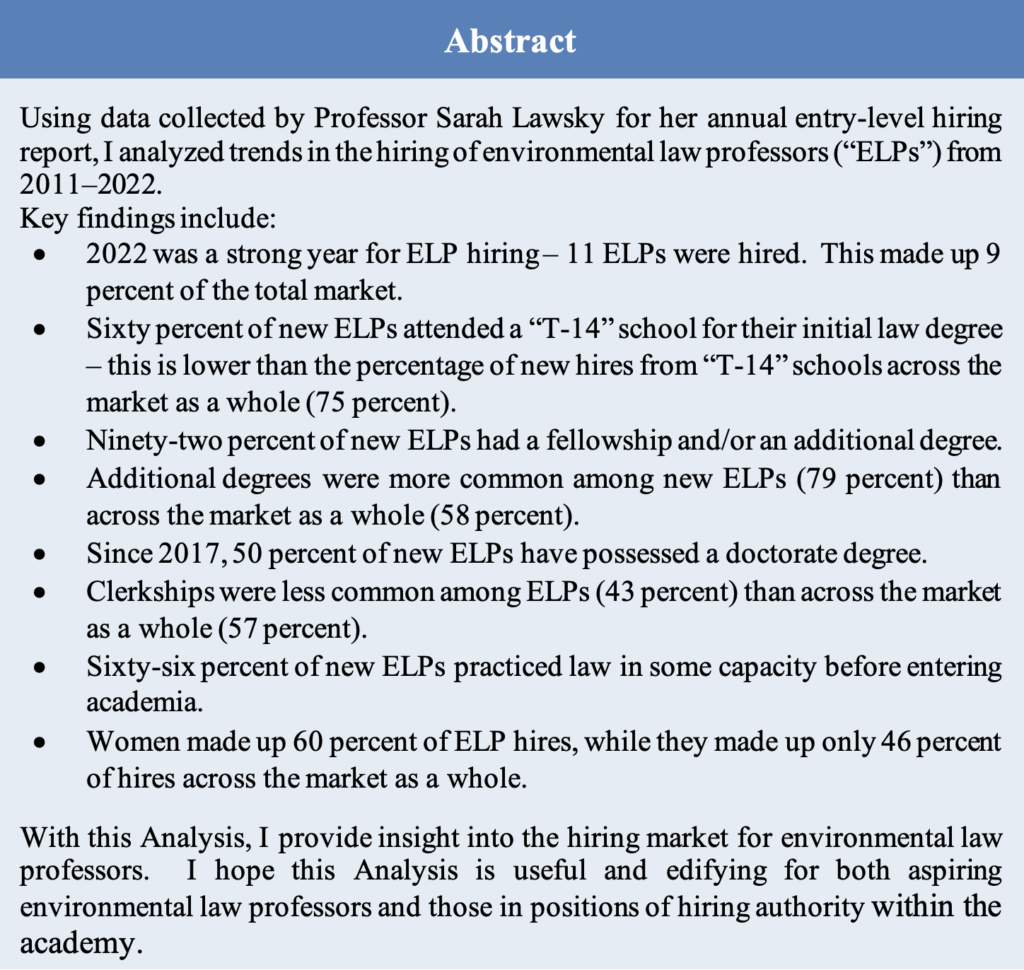

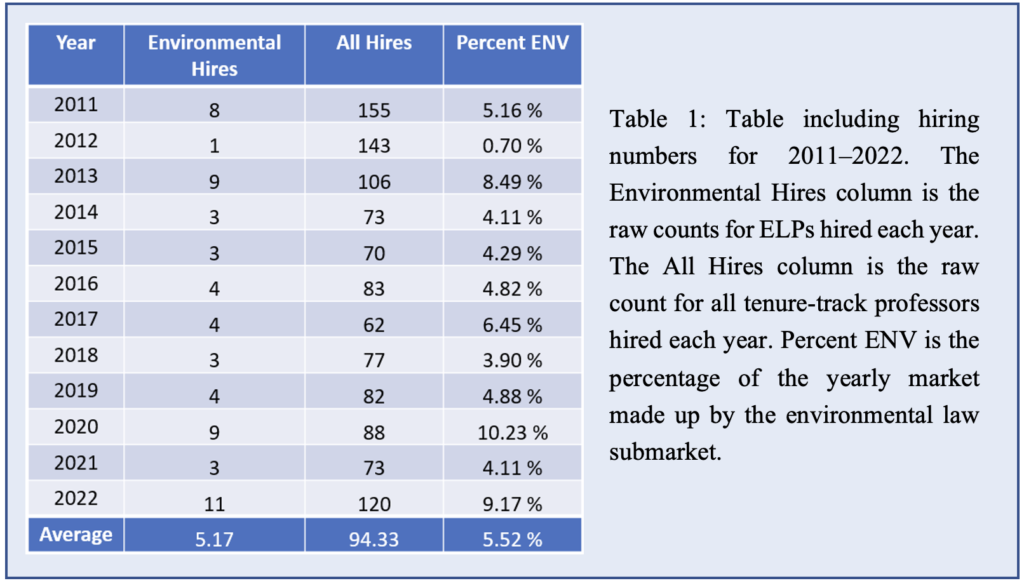

Since 2011, sixty-two non-clinical, tenure-track professors with an expressed interest in environmental law (ELPs) were reportedly hired (Table 1; Figure 1). During that same time period, 1,132 tenure-track law professors overall were reportedly hired, averaging about ninety-four per year. Notably, this average is heavily skewed by the period from 2011 to 2013. During those years, the market declined each year before stabilizing around 2014. Since 2014, the average number of hires each year has been only eighty-one. Further, 2022 was an anomalous year for the market as a whole, with more than 100 new professors hired for the first time since 2013.

On average, 5 percent of hires each year were in environmental law. Since the market dropped in 2014, three to four ELPs have been hired each year with just two outliers. ELPs have made up more than 8 percent of the market only three times, including two of the last three years. In 2013, 8.49 percent of the market were ELPs, likely explained by a rebound from the extremely poor year for ELPs in 2012 (ELPs were only 0.7 percent of the market). In 2020, nine ELPs were hired, and in 2022 eleven ELPs were hired (10 percent and 9 percent of the market, respectively).

It is too early to determine if this represents the start of a new normal or if these two years are merely outliers. However, one possible explanation for the increase is a large cohort of older professors leaving academia. As a field, environmental law is relatively young. Many of the titans of the field began their careers in the field back in the 1970s and 1980s. After years of service to the field, this original cohort of professors is retiring and opening up spots that need to be filled. Anecdotally, there have been several deaths, retirements, and faculty leaving academia (either permanently or temporarily) to work in the Biden Administration. A second potential explanation is that more schools are looking to hire in this area than before, likely due to student or institutional pressure to offer more environmental law courses. Many schools now offer robust environmental law curriculums, whereas before, environmental law could have been viewed as more of an elective.[9] With climate change and environmental justice becoming increasingly prominent in public discourse, increased demand seems like a reasonable explanation for the increase in hiring.

III. Initial Law Degree

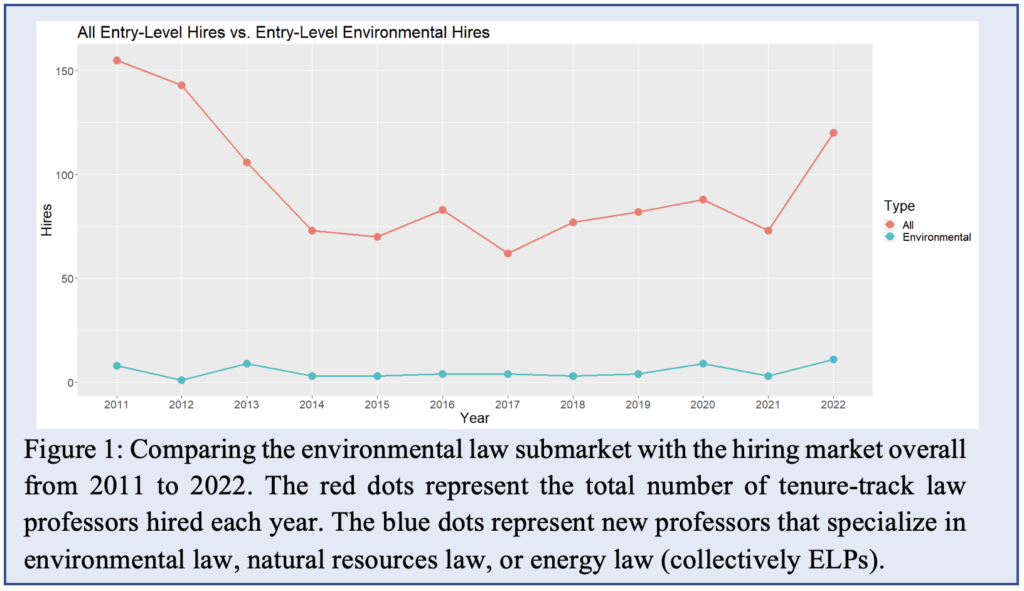

Traditionally, the institution where the candidate went to law school mattered greatly for success in the general market.[10] While no single school stood out, most ELPs attended highly ranked law schools (Figure 2). Only two schools have produced more than four ELPs since 2011: Harvard (six alumni) and NYU (six alumni). 60 percent (thirty-seven out of sixty-two) of new ELPs received their law degree from a “T-14” law school.[11] This is a smaller percentage than what was observed in the overall market (75 percent of non-ELP hires received their law degree from a “T-14” school), and this difference is statistically significant (p < 0.01).[12] This suggests that where a candidate went to law school, while still important, may matter less in the environmental law submarket than the overall market. On the other hand, 60 percent of the ELPs that did not attend a “T-14” law school (fifteen out of twenty-five) either earned an additional degree (i.e., a doctorate, master’s, or LL.M. degree) from a “T-14” law school or were fellows at a “T-14” law school.

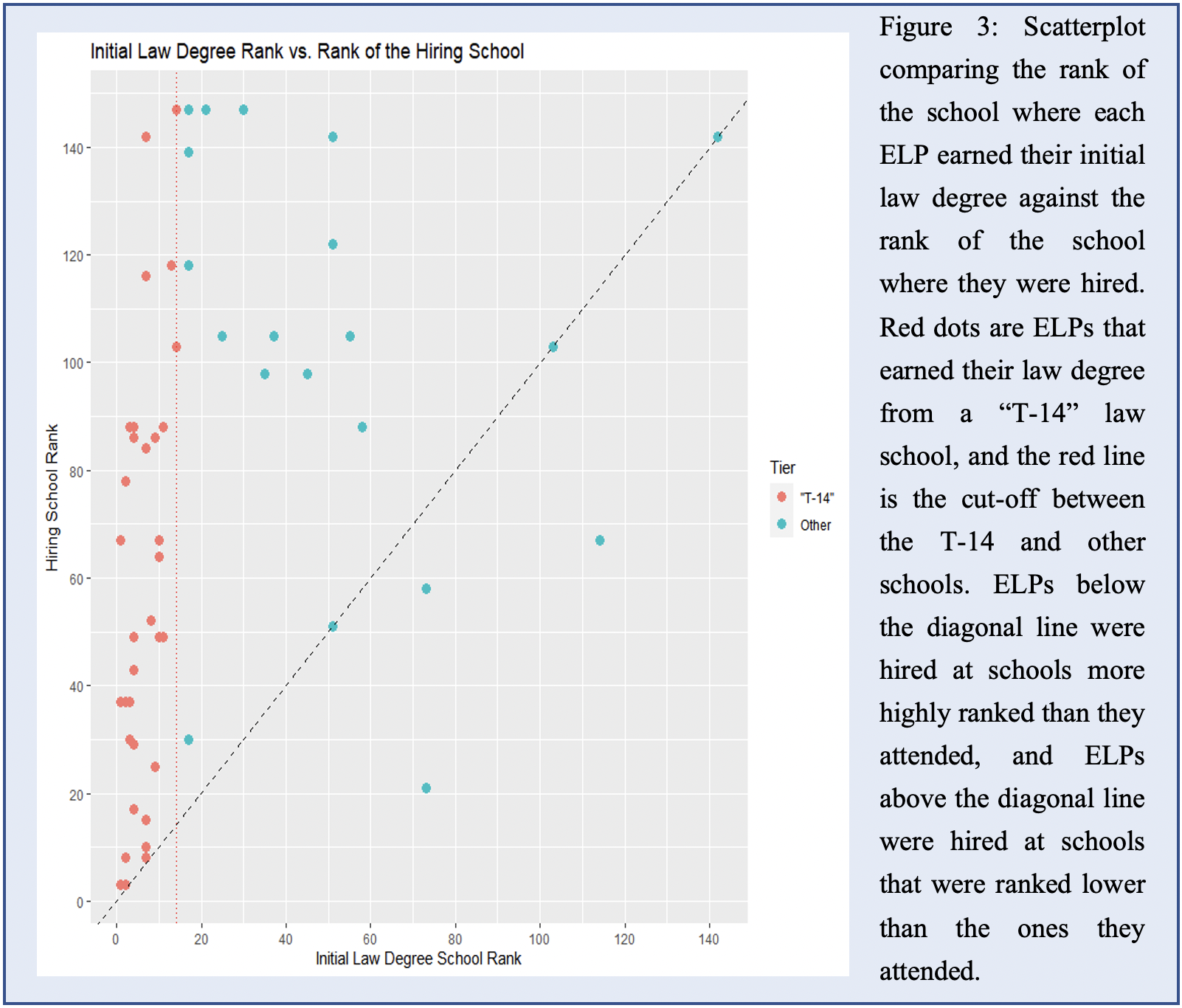

Further, the law school the ELP attended appeared to have a limiting effect on where they were ultimately hired (Figure 3). For example, twenty-one ELPs were hired by schools ranked within the top fifty law schools;[13] only two of those twenty-one ELPs did not attend a “T-14” school for either their J.D., J.S.D., or S.J.D. degrees. Lower ranked law schools were more willing to hire ELPs from outside the “T-14” schools – 54 percent (twenty out of thirty-seven) of ELPs hired by schools ranked above 50th did not attend a “T-14” school for their initial law degree. However, initial law school rank still played a role in ELP hiring; there was a strong preference for hiring ELPs that attended schools more highly ranked than the hiring school.[14] Only three out of fifty-four ELPs were hired at law schools ranked higher than the school the ELP attended.[15]

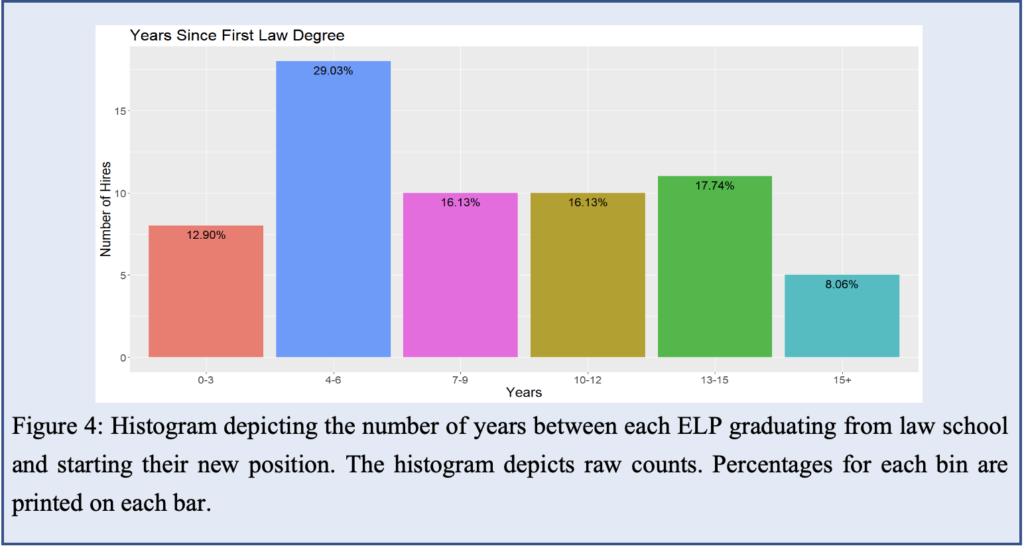

I also looked at the average time between graduating with an initial law degree and getting hired as an ELP (Figure 4). The average number of years between graduating from law school and getting a tenure-track job was about nine years, while the mode was five years. Two years was the shortest time between degree and initial hire, and twenty-four years was the longest time between graduation and hiring.

IV. Post-J.D. Credentials

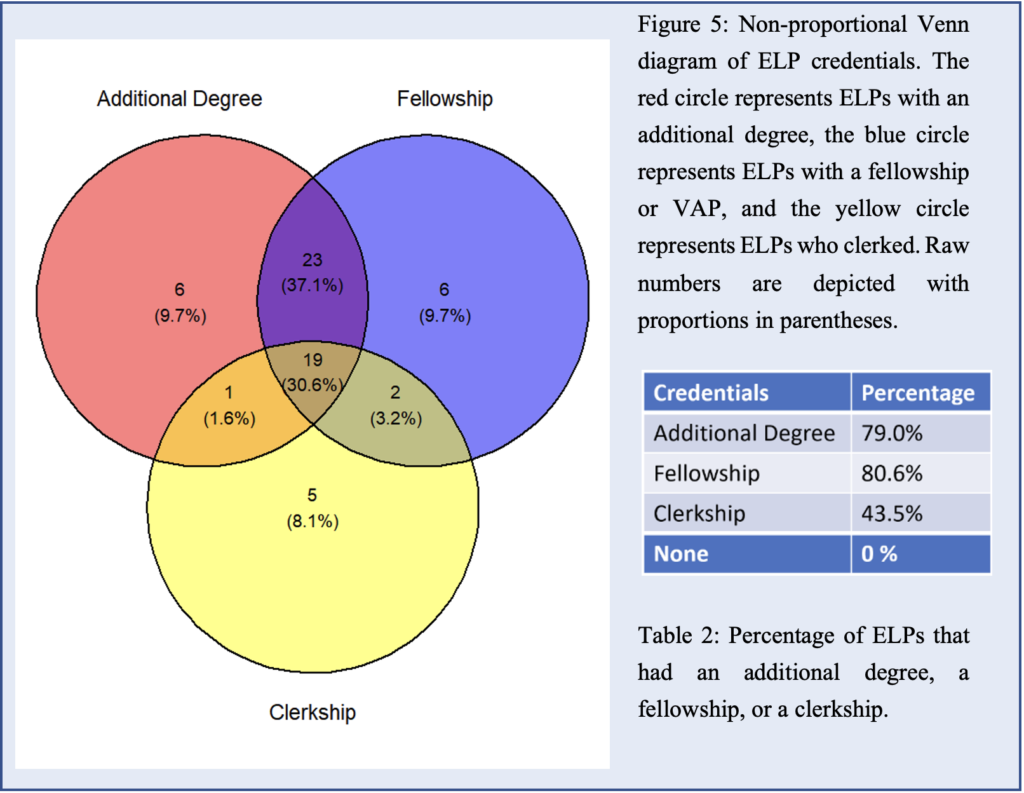

Prof. Lawsky’s data set specifically tracks three credentials: (1) additional degrees beyond the initial law degree, (2) post-graduate fellowships or VAPs, and (3) clerkships. Seventy-nine percent of new ELPs earned an additional degree, 81 percent of new ELPs had a fellowship or VAP, and 44 percent clerked (Table 2). The most common set of credentials was both an additional degree and a fellowship (37 percent; Figure 5). This was closely followed by having all three credentials (31 percent). Eighty-nine percent of ELPs have an additional degree and/or did a fellowship. Since 2011, no one has been hired as an ELP without at least one of these credentials.

V. Additional Degrees

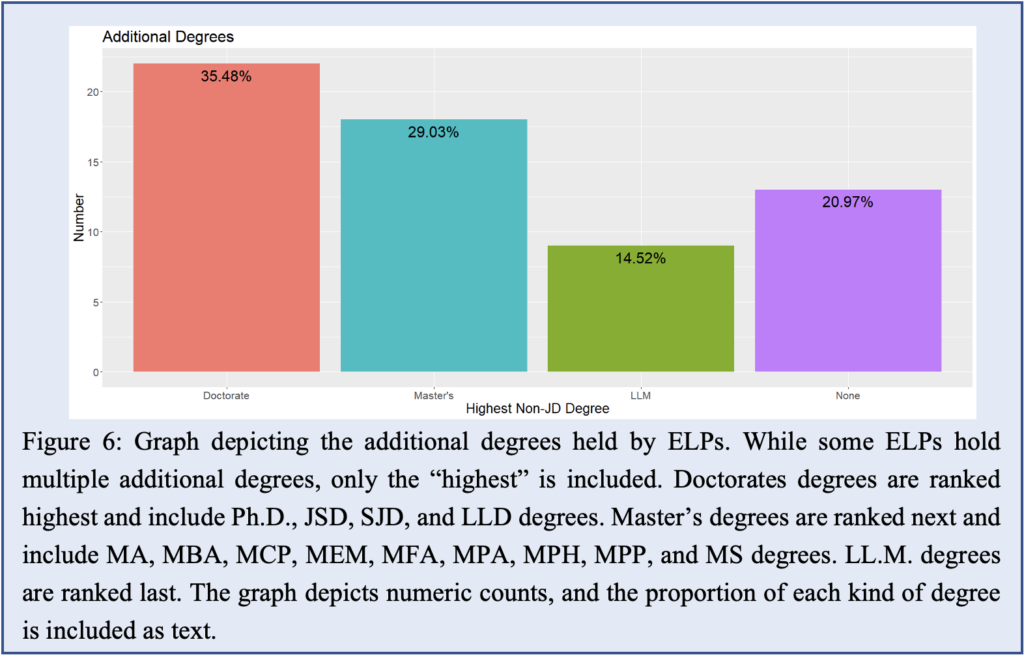

As stated, 79 percent of new ELPs earned an additional degree beyond their initial law degree. Since 2011 (Figure 6), there have been similar numbers of ELP hires with doctorate degrees (22) and master’s degrees (18), while L.L.M.’s were much less common (9). Thirteen of the new ELPs had no advanced degrees, outside of their initial law degree.[16] This is significantly different from the overall market (p < 0.001); 79 percent of ELPs hold at least one additional degree, while only 58 percent of non-ELP hires hold additional degrees.

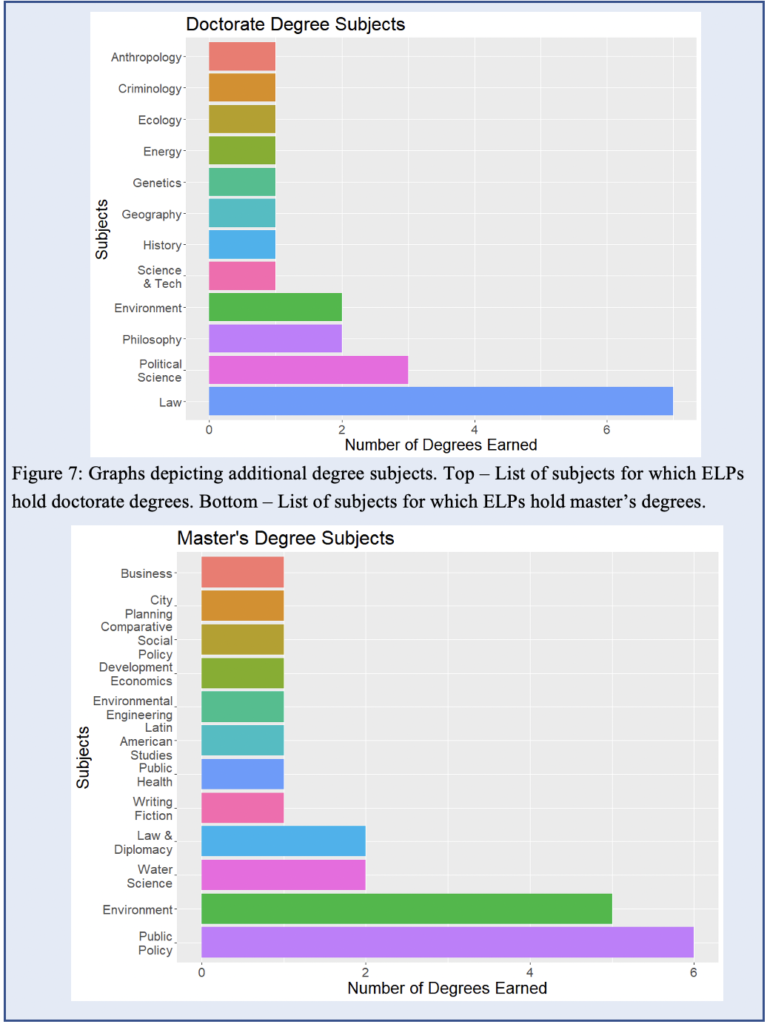

One explanation for the increased prevalence of additional degrees among ELPs is that environmental law, natural resources law, and energy law are all highly interdisciplinary fields, and expertise outside of law can be helpful for scholars in these fields. This is further reflected in the wide range of subjects represented by these additional degrees (Figure 7). While traditional law and law-adjacent subjects are heavily represented, many ELPs earned degrees in environmental science or policy. Further, there are both doctorate degrees and master’s degrees in the hard sciences (i.e., ecology, genetics, and water science) and the social sciences (i.e., anthropology, criminology, or geography).

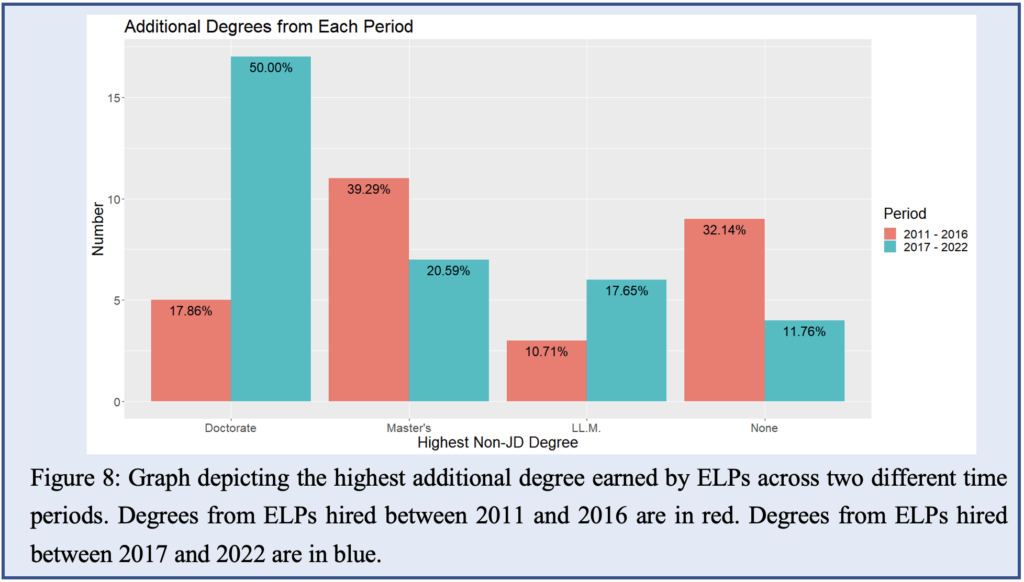

While the overall data on additional degrees is illuminating, the last twelve years might not represent the most recent hiring trends. Per Prof. Lawsky, the overall market has seen significant changes in the percentage of new hires with doctorate degrees.[17] For example, from 2011 to 2016, only 24 percent of new hires held doctorate degrees, but from 2017 to 2022, 46 percent of new hires held doctorate degrees. This trend is also seen in the environmental law submarket—significantly more ELPs hired in the last six years hold doctorate degrees (p < 0.01; Figure 8). From 2017 to 2022, 50 percent of new ELPs had earned doctorate degrees, but from 2011 to 2016, only 18 percent of new ELPs had earned doctorate degrees. Further, only 12 percent of ELPs hired from 2017 to 2022 had not earned an additional degree. In comparison, 32 percent of ELPs hired from 2011 to 2016 had not earned an additional degree.

VI. Fellowships

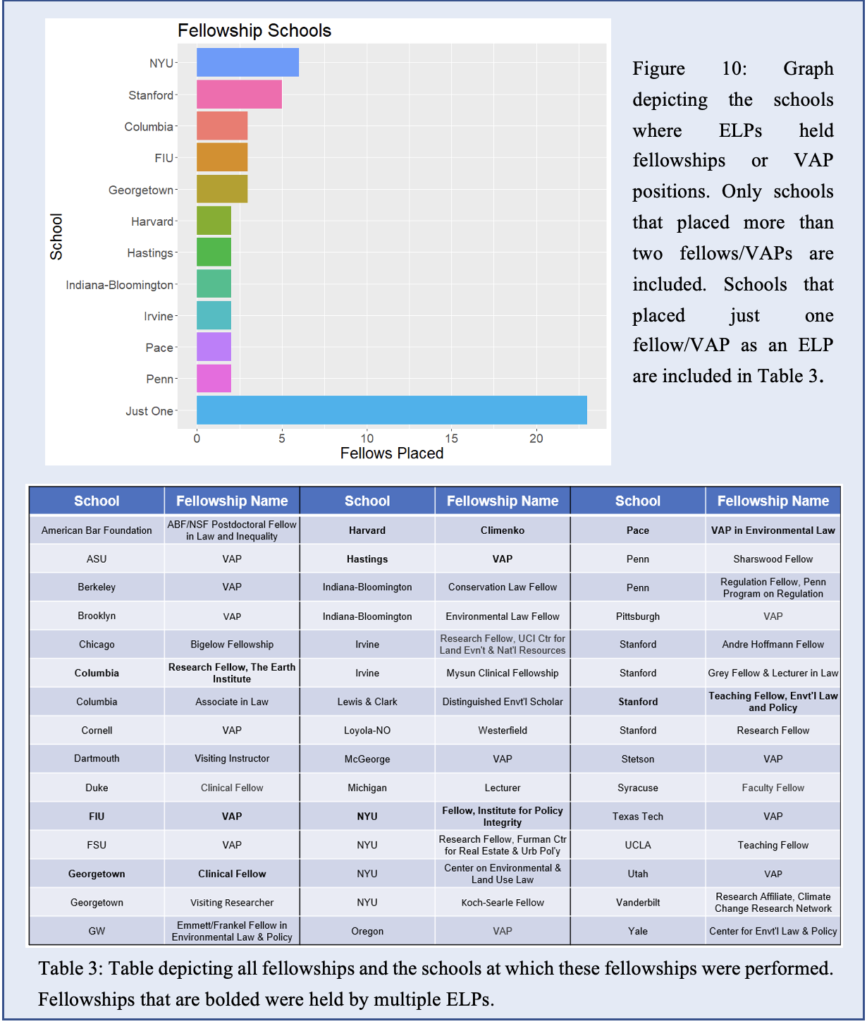

As previously reported, 81 percent (fifty out of sixty-two) of new ELPs had at least one fellowship or VAP position prior to getting hired. Additionally, five of those ELPs had two fellowships. Within the ELP dataset, there were fourty-five different fellowships at thirty-four different institutions (Table 3). Only NYU and Stanford have placed more than three fellows as ELPs since 2011 (Figure 10). This data suggests that fellowships are common among newly hired ELPs, but no fellowship stood out for placing the most fellows in environmental law positions. From 2013 to 2022, between 73 percent and 84 percent of all new hires had done a fellowship; thus, the ELP submarket is similar to the overall market in regards to the prevalence and importance of fellowships.

VII. Clerkships

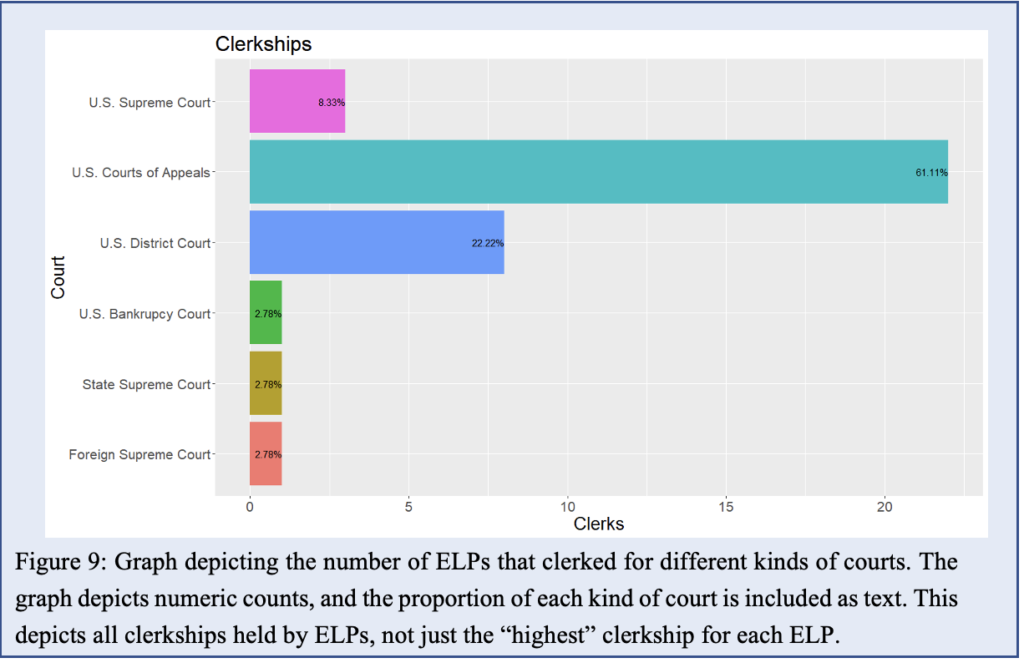

Only twenty-seven ELPs clerked, though some clerked multiple times. All but two of these clerkships were with U.S. federal courts, and the vast majority of ELPs that clerked did so at a U.S. Court of Appeals (Figure 9). ELPs clerked less than non-ELPs. Forty-three percent of ELPs clerked, while 57 percent of non-ELPs clerked, and this difference is significant (p < 0.04).

VIII. Practice Experience

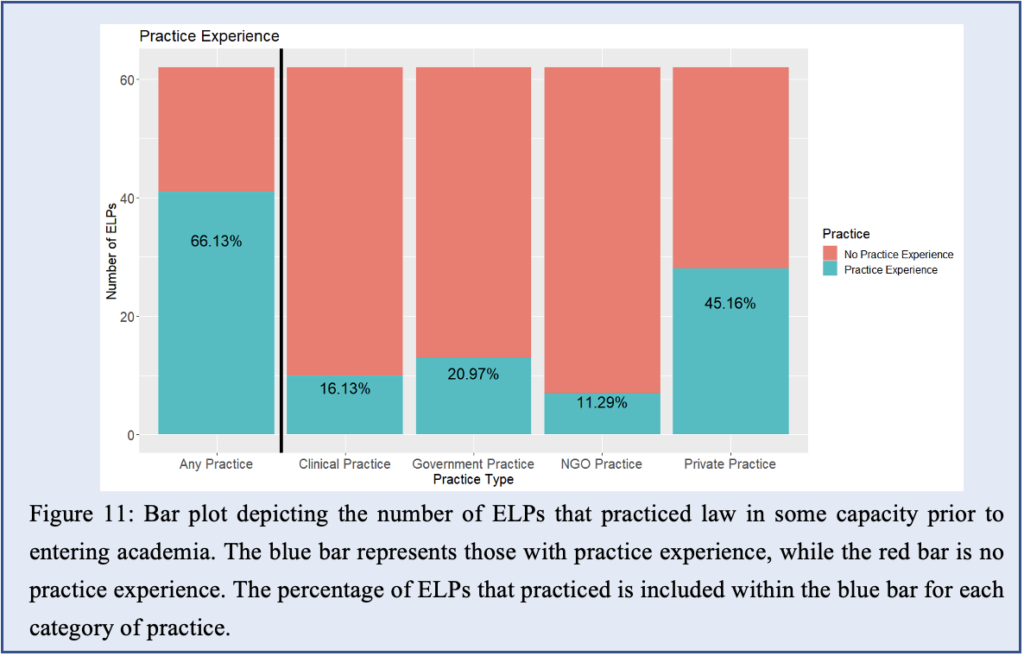

While Prof. Lawsky’s data does not include information on practice experience, I was interested in whether ELPs “practiced law” in some capacity before entering academia. I used faculty profiles on law school websites and associated CVs to determine practice experience.[18] I found that most ELPs (forty-one out of sixty two or 66 percent) did have some practice experience (Figure 11). Private practice (either in-house or at a law firm) was the most common type of practice experience (45 percent of ELPs), followed by government practice, practice in a law school clinic, and NGO/non-profit organization practice. Fourteen ELPs practiced across multiple settings. I was most surprised by the low number of ELPs that had worked for environmental interest groups before academia. While many ELPs were summer associates or interns for these organizations, only four ELPs practiced law for an environmental non-profit organization after law school.[19] Similarly, only seven ELPs worked for the federal or state government in an environmental agency or in environmental enforcement. In a field dominated by large public interest environmental groups and government agencies, I expected these groups to be better represented among recent ELPs.

IX. Gender of New Hires

Finally, I examined the number of women hired as ELPs. Since 2011, 60 percent of new ELP hires have been women.[20] This significantly differs from the overall hiring market (p < 0.01). According to Prof. Lawsky’s Reports, women have made up only 46 percent of overall new hires since 2011. Additionally, in the overall market, women have been hired more often than men only five times since 2004, and women have never made up more than 56 percent of the new hires in a year.

X. Caveats About the Data

As Prof. Lawsky makes plain with each report, this data is incomplete; it includes only hires reported via email or on the blog.[21] This data set is also limited to reported hires with an environmental law-related subject listed as a specialty area. Those subjects may not have been included for all professors that do environmental law scholarship and teaching. Additionally, some of the professors included in this analysis might not consider themselves “environmental law professors,” despite environmental law, natural resources law, or energy law being included as one of their four interest areas.

Further, the factors considered here are not intended to be exhaustive. I was only able to analyze the data that Prof. Lawsky collects each year, supplemented by what I could gather from faculty bios and available CVs. There are surely many other relevant factors that are not included in this data set. Publication record is likely the most important factor not analyzed. I attempted to gather this information from bios and CVs, but I ultimately found the exercise too subjective to be useful for analysis—it was difficult to determine both publication quantity and quality. Based on the long and variable timelines for publishing, it was impossible for me to determine whether a publication was available to hiring committees based on its publication year alone. Further, “publications” is a nebulous category that could conceivably include everything from law reviews and peer-reviewed scientific journals to blog posts and book reviews.

An examination of additional demographic information would likewise be edifying but was not possible based on the available sources of data. Many demographic factors that likely affect hiring, such as race, sexuality, disability status, or even political ideology, were not included in Prof. Lawsky’s data set and are impossible to determine based on faculty bios and CVs. A broader collection of data, collected in a standardized manner, would be needed to answer questions related to these other factors.

Conclusions

The environmental law submarket is generally similar to the market as a whole, with a few key differences. Most years, between 3 and 5 percent of new hires specialize in environmental law, natural resources law, or energy law. However, ELPs have been hired at nearly double the average rate for two of the last three years, though it remains too early to determine if this is a new trend or a mere anomaly. In general, ELPs were likelier to have an additional degree than non-ELPs. On the other hand, ELPs were less likely to have attended a “T-14” law school and less likely to have clerked than the rest of the market. These statistics support the idea that environmental and energy law scholarship is highly interdisciplinary. ELPs may prefer increased specialization in another field rather than further generalized legal training, such as clerkships. Like the overall market, there is a recent increase in new hires with doctorate degrees. Moreover, the vast majority of new hires were fellows or VAPs prior to getting hired. Two-thirds of ELPs had some sort of practice experience, and private practice was the most common form of practice. Finally, women were hired at higher rates in the ELP submarket than in the market as a whole.

I hope that aspiring ELPs will find this edifying rather than deflating. Many candidates, myself included, were hired without a perfect set of credentials. If you are considering going on the market in the fields of environmental or energy law, I hope this Essay will help you make decisions about how to best prepare. For current environmental or energy law professors, or anyone serving on a hiring committee, I hope this can inform the conversation about hiring in our field.

* Assistant Professor at Florida International University College of Law. B.Sc. in Biology and Biochemistry (2013), Washington and Lee University. J.D. (2018), James E. Rogers College of Law at University of Arizona. Ph.D. in Genetics (2020), University of Arizona. Former Visiting Assistant Professor in Environmental Law at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University. Thanks to Jason Czarnezki, Howard Wasserman, and Sarah Lawsky for their advice and encouragement on publishing this article.

[1]. See, e.g., Brian Leiter, Top Producers of Law Teachers at the Leading Law Schools Since 1995, Brian Leiter’s L. Sch. Rankings (Jan. 31, 2011), http://leiterrankings.com/new/2011_LawTeachers.shtml; Daniel Katz et al., Reproduction of Hierarchy? A Social Network Analysis of the American Law Professoriate, 61 J. of Legal Educ. 76 (2011); Tracey E. George & Albert Yoon, The Labor Market for New Law Professors, 11 J. of Empirical Legal Stud. 1 (2014); Asaf Lubin, The Initially-Foreign-Trained Law Student and the U.S. Legal Academic Job Market: A Survival Guide (May 25, 2020), http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3610025; Alexander Tsesis, The 2013 Full Hiring Report, PrawfsBlawg (Mar. 06, 2014) https://prawfsblawg.blogs.com/prawfsblawg/2014/03/2013-full-hiring-report.html.

[2]. George & Yoon, supra note 1 (analyzing the 2007–2008 hiring year and finding that having a JD from an elite law school, graduating from law school less than ten years before, having a publication in a top 100 ranked law review, having a judicial clerkship, and being a fellow/VAP at a law school were statistically significant predictors of receiving a tenure-track offer.).

[3]. Sarah Lawsky, Entry Level Hiring Report, PrawfsBlawg (Aug. 03, 2022), https://prawfsblawg.blogs.com/prawfsblawg/entry-level-hiring-report/.

[4]. Sarah Lawsky, Spring Reported Entry Level Hiring Report 2022, PrawfsBlawg (Aug. 03, 2022), https://prawfsblawg.blogs.com/prawfsblawg/2022/09/lawsky-entry-level-hiring-report-2022.html (enclosing the report from the 2021-2022 hiring year).

[5]. For example, Professor Jessica Erikson mentions this in her blog post on VAPs and Fellowships:

Having been on our hiring committee for many years, I will say that even though people talk about “the market” for law professors, there isn’t a single hiring market. Instead, there are many mini-hiring markets in various curricular areas. Picking on my own curricular area (I’m a corporate law person), the hiring market in corporate law looks really different than the hiring market in federal courts or con law.

Jessica Erikson, Final Reflections on VAP/Fellowship Interview Series, Becoming a L. Tchr. (Dec. 10, 2019), https://teach.aals.org/interviews/final-reflections/

[6]. The only recent example I am aware of is Prof. Asaf Lubin’s essay that focused on newly hired “initially foreign-trained” professors. See Lubin, supra note 1.

[7]. One notable exception is the yearly workshop held at Pace Law for aspiring environmental law professors. See Pace University, Future Environmental Law Professors Workshop, Pace Univ. (Sept. 9, 2022), https://law.pace.edu/future-environmental-law-professors.

[8]. Spreadsheet available here: https://tinyurl.com/2n2hvkbv.

[9]. In an admittedly back-of-the-envelope analysis, Prof. Dan Farber looked at a random subset of law schools to explore the extent of environmental law programs. Based on course catalogs, only one of the schools analyzed had fewer than two environmental law courses being taught. See Dan Farber, Environmental Law in US Law Schools, LegalPlanet (Aug. 1, 2022), https://legal-planet.org/2022/08/01/environmental-law-in-us-law-schools/.

[10]. Brannon P. Denning et al., Becoming a Law Professor: A Candidate’s Guide 24 (2010) (“Like it or not, the data says that the most important aspect of the Standard Model candidate is having received a J.D. from an Ivy League or Ivy League-equivalent law school.”).; see also George and Yoon, supra note 1.

[11]. The “T-14” here refers to: Columbia Law School; Cornell Law School; Duke University Law School; Georgetown University Law Center; Harvard Law School; New York University School of Law; Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law; Stanford Law School; University of California Berkeley School of Law; University of Chicago Law School; University of Michigan Law School; University of Pennsylvania Law School; University of Virginia Law School; and Yale Law School. 2023 Best Law Schools, U.S. News & World Report (Oct. 22, 2023), https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-law-schools/law-rankings.

[12]. All p-values were calculated using chi-squared tests comparing the ELP hires from 2011–2022 with all non-ELP hires during that same period.

[13]. All numerical rankings used here are based on the most recent 2023 US News and World Report Law School Rankings. Unranked schools were all given a ranking of 147. 2023 Best Law Schools, supra note 11.

[14]. Professors George and Yoon also documented this trend. See George and Yoon, supra note 1 (noting that only 1 percent (3/211) of new hires from 2007–2008 were hired by a higher tiered law school).

[15]. ELPs that were either hired by foreign law schools or that attended exclusively foreign law schools were excluded for this analysis as those schools were not considered in the USNWR rankings.

[16]. These statistics and the associated plots specifically represent the “highest” additional degree each candidate possessed. Some candidates possessed multiple classes of degrees or multiple degrees within the same class.

[18]. It can be difficult to draw a box around what “counts” as “legal practice,” and CVs and faculty bios are not necessarily the most forthcoming with details. I attempted to exclude research and non-attorney positions from this analysis.

[19]. Additionally, a few CVs mentioned that they represented these organization pro bono while in private practice. It is also worth mentioning that some of the law school associated clinics and centers work in conjunction with these organizations.

[20]. Though Prof. Lawsky reports on gender, her spreadsheets do not include that as a column. I used pronouns from faculty bios to determine ELP gender.

Yes, this spreadsheet is certainly missing some information. Repeat: this spreadsheet is incomplete. It represents only those entry-level hires that were reported to me, either through the comments on this blog or via email. It is without question incomplete. … This is just a report about self-reported entry level hires as of the spring before the school year starts.

Lawsky, supra note 3.